News

New guidance to help maximise climate change mitigation through the restoration of natural areas

News | Nov 2022

Megan Critchley, Programme Officer in UNEP-WCMC's Nature-based Solutions team, introduces comprehensive new guidance to help evidence the climate mitigation impact of nature restoration projects

Finding ways to mitigate climate change impacts is now an existential necessity.

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the contribution that landscape restoration makes to climate change mitigation, however, the links between climate change, biodiversity loss and restoration are often not well recognised in national policies and at high level events like the UN climate change conferences (UN Climate COPs). The Endangered Landscapes Programme (ELP) aims to restore natural areas across Europe that are in danger of degradation, showcasing real world examples of large-scale biodiversity conservation projects and how they can contribute to climate change mitigation efforts. With this work, UNEP-WCMC, in collaboration with the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and BirdLife International, highlight that biodiversity conservation can be a key tool to mitigate climate change, contributing to achieving the ambitions of the Convention of Biological Diversity and United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

As part of this work, UNEP-WCMC and partners developed a how-to guide to help restoration practitioners use two tools, the Carbon Benefits Project and EX-ACT, to quantify the climate change mitigation potential of ELP landscape restoration projects.

These tools are based on the guidance and methodologies from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and allow users to enter data about their projects to produce rapid assessments of climate mitigation potential, compared to a scenario where the project does not take place. These tools were originally created to assess the progress of projects focused on land management, but have been adopted in conservation projects due to lack of similar tools created for the field. However, they can be challenging to use for newcomers, making a how-to guide essential for people to understand them and apply them correctly.

Our new guidance allows restoration practitioners to better understand the ethos, tools, and methods that can be used to produce greenhouse gas balance estimates for ecosystem restoration actions. It is intended to cover the full process of the assessment, from selecting an appropriate tool, to collecting data, developing scenarios, and understanding the results. The goal is to enable restoration projects to better demonstrate their multiple benefits, even where climate change mitigation was not a core aim of the project. This evidence will then underscore the importance of climate change mitigation at the policy making level, improving support for projects, and potentially unlocking additional funding from donors and members of the private sector looking to invest in restoration projects as part of their net-zero targets.

The project team engaged with nine ELP projects to apply these tools and understand their suitability for use with large-scale restoration projects. These projects covered a diverse range of ecosystems and restoration interventions across Europe, such as peatland rewetting, grassland restoration, herbivore reintroductions, and reforestation. Through applying these tools, we were able to better understand their strengths and limitations and develop guidance to help practitioners through the process of these assessments.

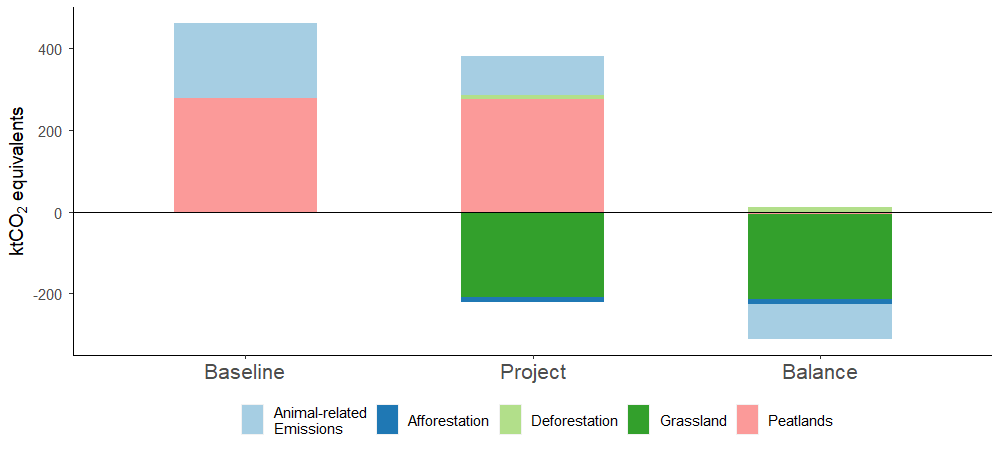

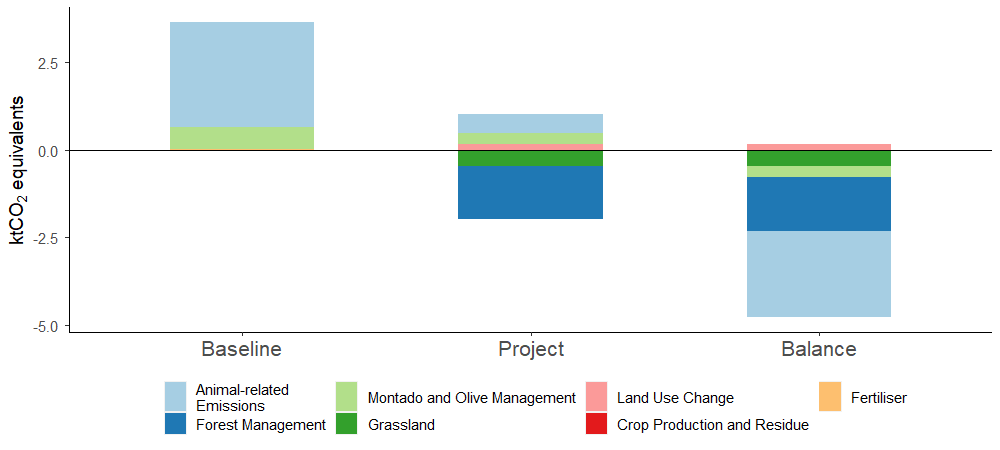

Within the new guidance, we aimed to select case studies which represented the breadth of ecosystems covered as well as a mix of geographical locations. Using the tools covered in the new guidance, we carried out assessments across these restoration projects, including the Cairngorms Connect project in the Cairngorms National Park in Scotland, and in the Greater Côa Valley in Portugal. Subsets of these projects were assessed, covering 31,200 hectares and 918 hectares of land respectively, and interventions carried out between 2000 and 2020. The interventions within the Cairngorms National Park had positive climate mitigation impacts, through restoring peatlands, and reducing the degradation of grassland through the reduction of deer grazing intensity. In the Greater Côa Valley, the assessment showed that emissions caused by animals and grassland degradation were substantially reduced between 2000 and 2020. Summaries for all projects can be found on the ELP website and in a webinar carried out by UNEP-WCMC and partners.

Our work further evidences how ecosystem restoration can have substantial benefits for climate change mitigation.

Despite some challenges, it is possible to apply assessment tools to quickly quantify the potential climate change mitigation contributions of large restoration projects. These assessments can help to demonstrate climate change mitigation as a substantial benefit of ecosystem restoration.

Have a query?

Contact us

communications@unep-wcmc.org